This post may be removed. It is very poorly writtten (I did it at 4 A.M.). Don't take everything in it was 100% correct and please mind any grammatical errors.

Chinese is easy. It is! Not just Mandarin, but most versions of Sinitic languages are easy. How is this, you ask? Well, just think about it this way.

In English we have prefixes and suffixes. We all know that "aqua" and "hydro" (depending on which origin you choose) both mean "water". So when we see a word that begins with one of these prefixes, we know it has something to do with water. Imagine the English language where all words are made up of prefixes and suffixes.

Let's imagine this for a moment. Let's take the word "simple" as an example. Imagine that for it's antonym, instead of using the word "difficult" we simply used the prefix "un" or "non" plus the word "simple", "unsimple" or "nonsimple". That's one less word that we have to memorize. This is essentially how Mandarin and other Sinitic (Chinese) languages work. Because they are based on a written language, simplicity is one of the key features in the language's grammar and syntax.

Just as English has prefixes, Chinese has semantic components and characters. The prefix "aqua" in English would most likely be represented by the semantic component 氵 or the character 水. Almost every character that you see with the component 氵 in it is going to have a connection with water or a liquid of some type.

Not only does Chinese have this unique feature to its written language, it is extremely logical. The word for "air conditioning" is 冷氣 or "cold air". And "air conditioner" is 冷氣機 or "cold air machine".

But wait, there's more! Chinese used to be 100% phonetic※ That's right, all phonetic. While there are today 214 main radicals (with some variants), there is another set of components used for pronunciation purposes. For example, the character 皇(huáng) is itself a character, however it is often used along with a semantic component to create a new character with a new meaning, but that is still pronounced huáng.

E.g. 徨、惶、蝗、煌、凰、etc.

While this is how the language was in the beginning, it is no longer 100% phonetic, rather it is now approximate. So while it may not be perfect, you can usually guess a words meaning or have a good idea what it is about, as well as know how to pronounce it a good part of the time.

So for those who think Mandarin or any Sinitic language is difficult, think again. The grammar is very simple and logical, and in many cases it is extremely similar to English grammar.

For those who think that the character system is too hard or has no reason to exist, think about this. When you write "air conditioning" you are writing a lot of letters. Let's break it down into "strokes". I count 27 "strokes" when I write the words "air conditioning". What's more, if you don't know what one word means, you don't know what the entire thing means. Now 冷氣(lěng qì) has 17 strokes total (11 in simplified Chinese) and gives us hints. The first character has the semantic component 冫(bīng) which means "ice", so it tells us that the character has something to do with either "ice" or something cold. The second character has the semantic component 气, which means "air" or "steam" and let's us know that the character has something to do with air.

So don't let this beautiful language scare you away, come join us and learn more about the rich and beautiful culture that is behind the Chinese languages, both written and spoken.

※ There are a number of characters that are not phono-semantic compounds. Read my post on different character types

here.

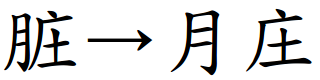

. Surprisingly this character is not included in most fonts, so don't be alarmed if you cannot see it on your computer. I will be using an image instead of the actual character to avoid any problems.

. Surprisingly this character is not included in most fonts, so don't be alarmed if you cannot see it on your computer. I will be using an image instead of the actual character to avoid any problems.

is pronounced tǐng. It is made up 丿(piě) and 土(tǔ, earth). Originally, this character was made from 人(rén, man, human) and 土(tǔ, earth) as you can see below.

is pronounced tǐng. It is made up 丿(piě) and 土(tǔ, earth). Originally, this character was made from 人(rén, man, human) and 土(tǔ, earth) as you can see below. (人) +

(人) +  (土) =

(土) =  (

( )

) is used.

is used.